Anaïs Nin au Miroir, written by Agnès Desarthe and directed by Élise Vigier,[1] was another production at the 2022 festival that sets off to investigate how an artist and an intellectual are made and function. Set in the backstage of a theatre cabaret, it focused on the enigmatic identity of Anaïs Nin (1903-1977), the French-Cuban writer and poet, known as one of the first female writers to specialize in erotic fiction.

Anaïs Nin au Miroir, written by Agnès Desarthe and directed by Élise Vigier,[1] was another production at the 2022 festival that sets off to investigate how an artist and an intellectual are made and function. Set in the backstage of a theatre cabaret, it focused on the enigmatic identity of Anaïs Nin (1903-1977), the French-Cuban writer and poet, known as one of the first female writers to specialize in erotic fiction.

A theatre company decides to explore Nin’s creative genius; so, it immerses into her books and memoires. They are working on a cabaret-like theatre show, an homage to Nin’s work. The questions they want to explore are: who was Anais Nin? What system of provocations and performative acts did she use to create her own literary persona? and What magic power does theatre possess to summon her on stage?

Here the stage itself becomes one of the major characters. Decorated with many frames that stand for the mirrors and the doors, the stage is both a rehearsal space and a place of performance. There are old furniture pieces, hangers for clothing, long tables, and a fake boat; all necessary theatrical props to create images and reflections of experiences, memories and desires evoked on the pages of Nin’s journals and books.

The show begins with a theatre janitor – a keeper of theatrical stories and secrets. She is sweeping the floors, when the young girl – supposedly Anaïs herself – enters her theatre space and so our journey into Nin’s dreams and into a theatre universe begins. This is the world of performative transformations and mutations: the mirrors and the projections hide and reveal Nin’s secrets, while the actors recite from her works and so connect the present time of this production, the world of the actors, with the world of the past and the world of her writing.

In addition to these purely theatrical devices, the shimmering illusions of Nin’s world emerge through a series of black and white projections, mostly the closeups of Anais, her mother, and her lovers. On screen, she is taking a trip along memory lanes. A theatrical boat we just saw on stage appears on the screen; the boat transports Anais, and us after her, from the reality of a theatre stage into the new reality of her onscreen presence. The truth of her personal experiences, however, remains as evasive as the staging. Was her mother as detached and as strict as she appears in Nin’s’ on-screen memory? Did the incestual relationship between Anaïs and her father take place? The only truth we can know for sure, this production seems to suggest, is that creating a theatrical illusion is similar to how our own experiences and memories are formed: much like in theatre, often our own experiences are shaped —whether we realize it or not—not by our needs, responsibilities and desires, but by our dreams.

Anne Théron’s performative rendition of Iphigénie (written by Tiago Rodrigues)[2] is another attempt at investigating the magic of theatrical transformations and transgressions. A new adaption of the story of the rise and fall of the House of Atreus, Rodrigues’ play offers an investigation of the premise of tragedy, a genre that always ends in someone’s death, as the Chorus of Angry young women states. The story of Iphigenia’s sacrifice, which begins with her father Agamemnon, who follows his egotistical whim and so subjects his daughter to death, has been retold many times. In Rodrigues’ version, the characters are liberated from their fate as it was predetermined by the gods’ will and authority. Each of them is given a chance to act as they please, i.e., to make their own choices. But neither of them can benefit from this new condition, and so they repeat their old actions and mistakes. Rodrigues’ Agamemnon is weak: he is unable to resist the pressure of history and his alleged heroic role in it, and, at the same time, he is crushed by his guilt, and by his understanding of his own fault. By contrast, this Clytemnestra is “an angry woman, determined to see Agamemnon answer for his crime before history” (Theron). But like her husband, she is also cursed by being trapped in the genre of the play: tragedy. Iphigenia as it seems is the only character who has a future in this world: she is in love with Achilles, the warlord, who believes in the life preserving power of his kisses. Neither of them, however, is given a second chance. Nobody can change the past: what we see, the Chorus insists, is a memory play; it is a memory of tragedy and desire. But who holds those memories together and to whom do they truly belong?

Memory, as Anne Théron seems to argue, is the material for transformation and a place for transgression: a balancing gesture between truth and fiction, between what has really taken place and what one has imagined about the past events. Moreover, memory, like theatre, can cast different people in different roles and make them change their stories.

Language – the words spoken at the audience, not to each other – leads this story forward. Agamemnon states that he never cried over the fate of his daughter; the Chorus insists – he did. The dialogue unfolds slowly; and in its monotonous musicality, it reminds of dripping water, the sound able to enthrall its listeners. An empty stage and a series of slowly moving projections constitute the major feature of this production’s décor. As the action unfolds, the images of flickering waves and of the grayish shadows transform into the purple colours of thunderous skies and finally into a profile of a young girl, whose untimely and uncalled for death makes her features disappear in front of our eyes. Her face, projected onto the backdrop, becomes indiscernible in the time and space of history, but also within the production coming to its finale.

Like many other productions of the Avignon 2022, this Iphigénie reveals similarities between the illusory and fragile nature of memories and the fictional constructions a theatre performance is called to create. The action takes place on the theatre stage, but also at the tidelines of dream and reality. The characters are trapped in the aftermath of tragedy – both the history of its interpretations, and the history of civil wars, when it would not be uncommon for parents to sacrifice their children for the sake of their own chimeras and pride. This is the time of a standstill, but how long will it last, and for whom is the next bell going to toll?

My last two examples of the Avignon 2022 rendition are Amir Reza Koohestani’s En Transit[3], based on the novel by Anna Seghers, and Bashar Murkus’s Milk[4] – both unapologetically political, asking their audiences to recognize the transgressive power of theatre to speak of the tragedies of today.

My last two examples of the Avignon 2022 rendition are Amir Reza Koohestani’s En Transit[3], based on the novel by Anna Seghers, and Bashar Murkus’s Milk[4] – both unapologetically political, asking their audiences to recognize the transgressive power of theatre to speak of the tragedies of today.

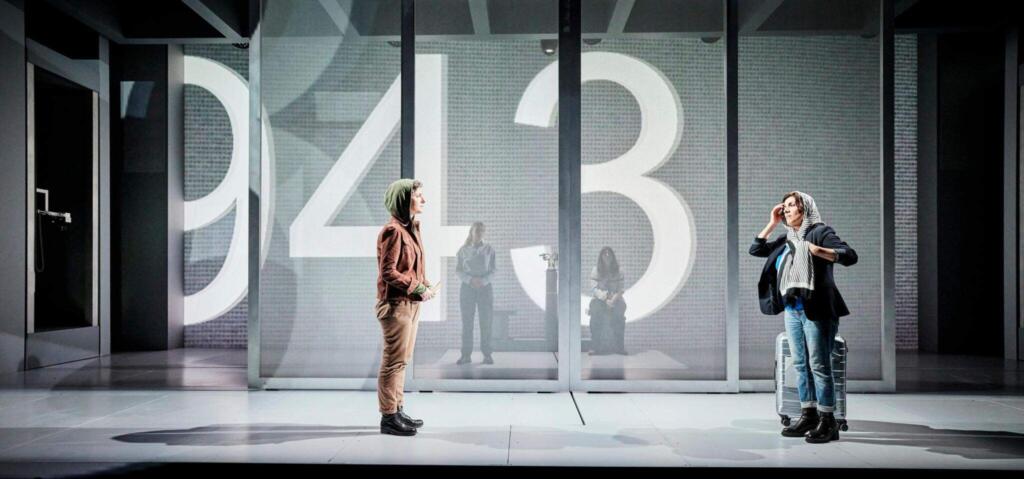

Inspired by Anna Seghers’ novel and his own experiences in global traveling, Koohestani recreates an unsettling story of being stuck in the transit zone of an international airport, being lost between places and times, between arbitrary administrative requests and regulations that a refugee or an unwelcome traveler may face. The action unfolds in two temporal and spatial zones: one story takes place in 2018, in Munich, and recounts Koohestani’s own encounter with the border control officers. On his way from Iran to Chile, Koohestani was stopped by the Munich airport’s border guards and transferred to its transit zone. After having spent several days in the limbo of this “waiting area”, Koohestani was told that his Schengen visa has expired and he must go back home, even though he had another visa which would legitimize his traveling itinerary. This experience served the artist as his inspiration to create a theatre play about the notions of exile, transit, and nationalism. While waiting in the airport, Koohestani happened to be reading Anna Seghers’s novel Transit, which describes the story of Jewish exiles who were trying to escape Nazi Germany, and their troubles as they were getting mired in the bureaucracy of the 1930s Europe. Ironically, Koohestani observed, nothing has really changed between the events, the circumstances and the injustices of the 20th century Europe and the world of today. To reflect on this sad realization, he put together a multilingual cast of female performers to enact an improbable meeting between the characters from Seghers’ novel and a contemporary theatre director trapped in the Munich airport.

To emphasize the maddening circumstances of this story and the impersonality of the airport’s transit zone, Koohestani placed his characters on an empty theatre stage. Several glass cubicles, which soundlessly and effoltressly appear on and move away from this stage, create additional acting spaces for the characters to communicate with each other but also to signify being trapped in their own time and misery. The sterility, the coldness and the detachment of this transit zone were to remind Koohestani’s audiences of the impersonality of the bureaucratic systems, which every refugee, asylum seeker or migrant encounters when they seek help from the authorities of their would-be host country. Being trapped in the cubicle also serves as a temporal metaphor: we cannot reach the past and the past cannot truly speak to us, even if a theatre stage becomes the welcome space for such illusory transgression. This visual statement, I argue, reinforced another troublesome lesson of history: even though many problematic experiences of today (including forced migration and wars) are similar to those that took place in the past; history does not seem to teach us any lessons. The humankind can only repeat its own mistakes, even if artists and intellectuals continue bringing this truth to our attention. The past can give us examples, but can we learn anything from them?

Bashar Murkus’s Milk continued this conversation about the unlearned lessons of history. A movement- image-based composition, it created visions of modern tragedy and commented on the vicious circle of life and death as experienced by mothers who lost their children to war conflicts, hunger, or natural calamities. With its opening image of the group of mothers holding life-size dummies used by medical students to study human anatomy, as their dead children, Milk was one of the most emotionally challenging productions I saw in this rendition of the festival. It created a series of scenes and images in which mothers would both bear and lose their children, and it spoke of no endi to their terror and grief.

The title of this performance – Milk – refers to what Murkus sees as the foundation of life but also of its destruction. From the very first scene, in which the mothers fail to bear the weight of their dead children, to the last one, in which they try to save the only living child played by the only male performer in the group, these mothers rely on the power of milk. The action begins in the emptiness of a bare theatre stage, which the mothers gradually transform into a well of life filled with their milk. An image of time, this transformation itself, as Murkus explains, “reminds us that the consequences of the disaster have long repercussions on our lives. They influence the present, change our perceptions, our conscience, just like they change and influence the physical world around us. Paradoxically, it also allows [the artist – YM] to talk about the beauty of the world through the way women transform the stage into a marvelous landscape in order to escape death, better domesticate its effects, and tame violence” (Interview)[5]. The milk these mothers produce serves both as a source of life and as a way to grieve the death that surrounds them. Death is indeed one of the central themes in this performance: “our relationship to death”, “how we understand it, how we approach it from a political, but also medical or religious point of view” (Interview) constitutes a set of questions that the director wants to ask. But it is also about the mother’s body: the death of her child changes the mother’s body; it takes away her energy. But there are many different bodies on this stage: some of them are simply unloved and undesired, whereas others are made invisible or forgotten. For Murkus, these are the “living bodies” that many political systems “hide, keep away, or exile” (Interview). This juxtaposition of the living and the dead creates a new “visual and dramaturgic power” on stage; but it is also a pure metaphor, something that the director puts forward but refuses to explain or analyze.

In its visuality, this astonishing production refers both to the Christian iconography, from Pieta paintings to those of Christ’s descent from the cross, and references the fertility and rebirth rituals from the Middle East. Paradoxically, however, in its privilege of a theatrical metaphor, Milk, as many other productions at the Avignon 2022, refuses to directly comment on our reality, defined by the world’s disasters, environmental catastrophes, and civic wars.

Milk, similarly to other productions I was able to see this year, speaks back to Olivier Py’s motto for the 2022 festival, which unlike its pre-Covid edition of 2019, seems to focus on the questions essential for making theatre and the value of the encounter between the stage and the audience in the world of multiple “posts”: post-truth, post-pandemic, post-democracy and post-peace. This new post-pandemic theatre, it seems to me, invites its audiences to rediscover the power of creating magic, making and breaking theatrical illusions; in this it reinstates the attraction of live theatre, something that it is so famous for.