I arrived at the 2022 Avignon Theatre Festival seeking emotional rejuvenation after two years of COVID related isolation, working on screens, and deprived of live encounters in theatre; but also shattered by the war in Ukraine and realization that the world I have known, specifically in Europe, has dramatically changed. I expected that what I would see at the festival would inevitably speak back to these global disasters, albeit very different ones. To my surprise, among a dozen of productions that I was able to see during the first week of the festival only a few, such as En Transit by Amir Reza Koohestani, Milk by Bashar Murkus, and One Song, Histoire(s) du Theatre IV by Miet Warlop – spoke to these new realities of today. Others seemed to be focused on the dilemmas, issues, and troubles pertinent to making theatre both as an art form and a type of philosophy, and the issues relevant to each individual theatre maker, who presented their work at the festival. Perhaps, one could argue, the Avignon 2022 tried to advocate a vision of “theatre against politics”, an idea argued by Olivier Neveux in his recent book Contre le théâtre politique (2019). To Olivier Py, who in July 2022 stepped down from his role as an artistic director of the Avignon Theatre festival, this edition was a chance to pay homage to the festival’s original conceptualization as envisioned by Jean Vilar in 1947. For the 2022 edition, Py chosethe slogan “Il Était Une Fois”/”Once Upon A Time” as the festival’s focus theme. To that end, he programmed a number of new versions of the Western theatre classics, including Kirill Serebrennikov’s take on Anton Chekhov’s short story Le Moine noir, Anne Théron’s staging of Iphigénie (in adaption by Tiago Rodrigues, the incoming artistic director of the festival in 2023), Alessandro Serra’s La Tempesta, and, among others, Samuel Achache’s Sans Tambour, a theatrical burlesque based on Schumann’s music, called to offer help to Achache’s characters and audiences when facing the troubles of the broken heart, separation, and personal collapse. Other works seemed to be interested in studying the power of theatrical transformations (like Anaïs Nin au Miroir directed by Élise Vigier or a 13-hour epic Le nid de Cendres, Integrale created by Simon Falguières), and creating more space for the text-based theatre, like Dans ce Jardin qu’on aimait by Marie Vialle. This list, however, is far from comprehensive to fully grasp the essence of the Avignon 2022, although, I think, it is representative of the tendencies and directions it was programmed to explore. From this point of view, Olivier Py’s original work Ma jeunesse exaltée can be seen as a philosophical anchor of this edition.

I arrived at the 2022 Avignon Theatre Festival seeking emotional rejuvenation after two years of COVID related isolation, working on screens, and deprived of live encounters in theatre; but also shattered by the war in Ukraine and realization that the world I have known, specifically in Europe, has dramatically changed. I expected that what I would see at the festival would inevitably speak back to these global disasters, albeit very different ones. To my surprise, among a dozen of productions that I was able to see during the first week of the festival only a few, such as En Transit by Amir Reza Koohestani, Milk by Bashar Murkus, and One Song, Histoire(s) du Theatre IV by Miet Warlop – spoke to these new realities of today. Others seemed to be focused on the dilemmas, issues, and troubles pertinent to making theatre both as an art form and a type of philosophy, and the issues relevant to each individual theatre maker, who presented their work at the festival. Perhaps, one could argue, the Avignon 2022 tried to advocate a vision of “theatre against politics”, an idea argued by Olivier Neveux in his recent book Contre le théâtre politique (2019). To Olivier Py, who in July 2022 stepped down from his role as an artistic director of the Avignon Theatre festival, this edition was a chance to pay homage to the festival’s original conceptualization as envisioned by Jean Vilar in 1947. For the 2022 edition, Py chosethe slogan “Il Était Une Fois”/”Once Upon A Time” as the festival’s focus theme. To that end, he programmed a number of new versions of the Western theatre classics, including Kirill Serebrennikov’s take on Anton Chekhov’s short story Le Moine noir, Anne Théron’s staging of Iphigénie (in adaption by Tiago Rodrigues, the incoming artistic director of the festival in 2023), Alessandro Serra’s La Tempesta, and, among others, Samuel Achache’s Sans Tambour, a theatrical burlesque based on Schumann’s music, called to offer help to Achache’s characters and audiences when facing the troubles of the broken heart, separation, and personal collapse. Other works seemed to be interested in studying the power of theatrical transformations (like Anaïs Nin au Miroir directed by Élise Vigier or a 13-hour epic Le nid de Cendres, Integrale created by Simon Falguières), and creating more space for the text-based theatre, like Dans ce Jardin qu’on aimait by Marie Vialle. This list, however, is far from comprehensive to fully grasp the essence of the Avignon 2022, although, I think, it is representative of the tendencies and directions it was programmed to explore. From this point of view, Olivier Py’s original work Ma jeunesse exaltée can be seen as a philosophical anchor of this edition.

An epic farce of 10 hours, Ma jeunesse exaltée served both as Olivier Py’s goodbye show to his nine-year career (starting from 2013) as the head of the Avignon Festival and an homage to his first appearance at the festival with a 27-hour opus La Servante, in 1995. At the centre of Ma jeunesse exaltée is Harlequin, played by Bertrand de Roffignac, whose “energy, grace and charisma were a source of inspiration” for Olivier Py (//www.lesechos.fr/@philippe-chevilley" style="box-sizing: border-box; margin: 0px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; font-style: normal; font-variant-ligatures: normal; font-variant-caps: normal; font-variant-numeric: inherit; font-variant-east-asian: inherit; font-weight: 400; font-stretch: inherit; font-size: 16px; line-height: inherit; font-family: "Playfair Display", Georgia, "Times New Roman", serif; vertical-align: baseline; color: rgb(205, 42, 57) !important; text-decoration: none; word-break: break-word; overflow-wrap: break-word; letter-spacing: normal; orphans: 2; text-align: start; text-indent: 0px; text-transform: none; white-space: normal; widows: 2; word-spacing: 0px; -webkit-text-stroke-width: 0px; background-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);">Chevilley 2022) [2]. “Harlequin is the symbol of theatre”, Py explains (Interview)[3]. He is surrounded by the representatives of the French political elite and society, cast as the famous comedic stock characters from the French farce. Under Harlequin’s spell, the stage of Lycée Aubanel turns into a theatre phantasmagoria put in motion by ten actors and two musicians. Ma jeunesse exaltée is also a meeting point for several generations of actors: those who appeared in La Servante, including Céline Chéenne, and the newcomers to the festival. In other words, Ma jeunesse exaltée can be seen both as Olivier Py’s love letter to the theatre, a celebration of its mystic force, and a record of the artist’s personal pilgrimage through the magic of performative and life transformations.

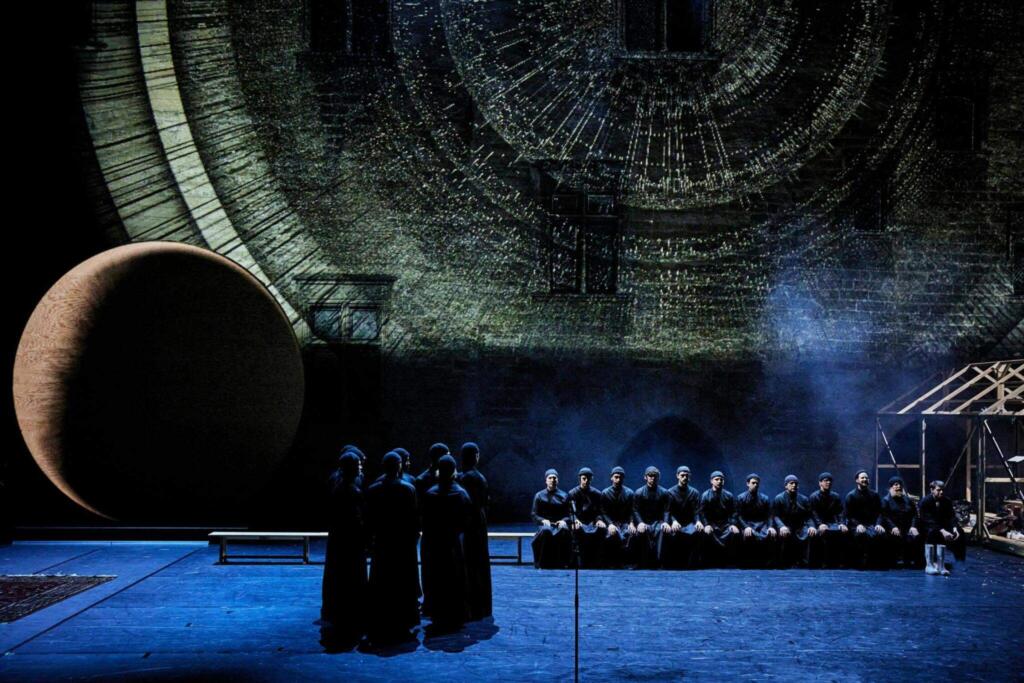

Kirill Serebrennikov’s Le Moine noir / The Чёрный Mönch, which opened the 2022 festival in the legendary Cour d’honneur of the Palais des Papes[4], expressed similar to Py’s focus on the power of not only theatrical and spiritual transformations but also transgressions.

Kirill Serebrennikov and his production arrived in Avignon amidst the hype of the latest political and cultural events. Russia’s unlawful invasion of Ukraine and subsequent protest reactions around the world to this invasion, including calls to stop collaborating with Russian cultural institutions and individuals, were on the minds of many festival’s attendees. Launching Serebrennikov’s most recent film Tchaikovsky Wife at the Cannes Festival added to this already electrified air of festival’s anticipations. The film, which was the only Russian work presented at the 2022 Cannes, was highly praised by its critics and viewers, while Serebrennikov’s press-conference managed to steer polarized feelings of admiration, compassion, and anger. The influential French scholar of the Russian theatre, Béatrice Picon-Vallin, summarized these frustrations in her article «À propos de Kirill Serebrennikov : se poser les bonnes questions ». There she questioned Serebrennikov’s moral stance and demanded that the director clearly state his political position apropos the war in Ukraine as well as to reveal the sources of his works’ financial support (2022)[5] . At the same time, the memory of the so called “theatre trial” (June 2020), in which Serebrennikov was wrongly accused of financial fraud, his home arrest and subsequent firing from the position of Artistic Director of his theatre company in Moscow, Gogol-Centre (2021), were still fresh in the minds of the Avignon audiences. On top of all that, on June 29, 2022, a couple of days before the opening of the festival, the Moscow Department of Culture announced that “the contracts with the current artistic director and director of Gogol Center would not be extended” [6]. The statement meant the only possible outcome: Serebrennikov’s theatre was ordered to be closed, while its name Gogol-Centre to be reverted to the original “Gogol Theatre”, and thus cancelled out from history. The closure of the Gogol-Centre, some of whose actors were cast in Le Moine noir, was the final blow to the practices of creative and political freedom that Serebrennikov’s work had come to signify in Putin’s Russia.

Olivier Py, who invited Serebrennikov to stage an opening production of the Avignon 2022, happened to be a longstanding supporter of this artist’s work. Py supported Serebrennikov through his career, with Les Idiots and Les Âmes mortes programmed at the festival in 2015 and 2016 respectively. In 2019, Py also welcomed Serebrennikov’s Outside, one of the few productions that the director staged remotely, while he was forced to stay under the house arrest. Thus, this highly controversial context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its repressive politics at home and Serebrennikov’s personal story of resistance and persecution added to the hype-like atmosphere in which Le Moine noir opened on the first night of the festival.

A multilingual production (Le Moine noir played in German, English and Russian with surtitles in French and English for the Avignon audiences), this was Serbrennikov’s second take on his own adaptation of Chekhov’s short story. Originally staged for the Thalia Theater in Hamburg, in January 2022, the Avignon’s Le Moine noir had to be significantly adapted in its visual language and technology to the space and time of the festival. It also revealed more about the director’s philosophy and artistic preoccupations than about his politics that used to drive many of his other works forward. One could argue that Le Moine noir charted what might become the next chapter in Serebrennikov’s creative path and laboratory. Now dedicated to the magic of theatrical transgression, the ways performance arts allow the realities of the beyond to penetrate our own world, Serebrennikov’s Le Moine noir turned into a celebration of the history and the magnificence of the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des Papes with the cold and powerful mistral winds blowing through it. It also surprised the connoisseurs of Serebrennikov’s theatre and directorial style. Often based on a mixture of pamphlet-like visual statements and evasive theatrical metaphors, Serebrennikov’s work – from his early staging of Vassily Sigarev’s Plasticine to a more current Outside – would offer the director’s criticism of the corruption, the hypocrisy and the hate that make up Russia’s politics and style of governance. On the contrary, Le Moine noir displayed none of these openly political statements or criticisms. It focused on the figure of a lonely individual – an outsider of some sorts – who is afraid of losing his intellectual and spiritual independence. The protagonist Kovrin’s battles were first of all of spiritual nature and focused on one’s encounters with the beyond. To a certain degree, I would argue, the spectators of the 2022 Avignon festival were disappointed but also privileged to meet another Kirill Serebrennikov, not the protagonist of political tabloids, but a deeply wounded artist, courageous enough to expose on stage his own spiritual uncertainties and dark demons.

Like in Chekhov’s original short story, at the center of Serebrennikov’s adaptation is the intellectual Kovrin, who first loses faith in his own intellectual output and then his mind. Seduced by the promise of domestic happiness, Kovrin marries Tanya, the daughter of his former tutor and spiritual guide, the gardener and scientist Pesotskiy. With time, Kovrin realizes that he is not made for this type of life, and he is not content. Kovrin begins to slowly lose his mind. He leaves Tanya and dies in an asylum, fully immersed in his deliriums. The figure of Black Monk, who visits Kovrin during his visions and nightmares, is the title character of both Chekhov’s short story and Serebrennikov’s performance. As Kovrin’s deliriums intensify so does the presence of the monk both on the pages of Chekhov’s story and on Serebrennikov’s stage. Unlike in the original, however, in Serebrennikov’s adaptation the story of Kovrin’s downfall is repeated four times: first it is told from the perspective of Pesotskiy, then of Tanya, then of Kovrin himself, and finally that of Black Monk. With each repetition, the logic of the events loses its rationality. The action becomes more surreal, when finally, Black Monk and his multiple doubles, represented by a group of male dancers, dressed in the swirling black skirts, and chanting and moving in unison, takes the center stage.

As the action unfolds, Kovrin changes too. In the first part, Kovrin speaks German and is played by Mirco Kreibich, one of the leading actors of the Thalia Theater. His story is told from the perspective of Pesotskiy (Bernd Grawert), who in his scientific approach to the world exhibits positivist and patriarchal modes of thought and behavior. Here, Kovrin is an intellectual who suddenly realizes the futility of his work. Recently, he says, his thinking has lost its depth, focus, and necessity. What he now writes are journalistic petitions, pamphlets, and letters of protest for political causes. This is the crisis of an intellectual: something that might speak to the feelings of frustration and guilt that many Russian intellectuals and artists feel today, when they realize that despite their continuing political resistance, they have been unable to stop the war their government started or to turn back history. Pesotskiy controls the universe of this version of Kovrin’s story. A gardener, he lives by a set calendar with sunrises and sunsets, which in turn dictates his course of actions. An echoing of the character Lopakhin from Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, Pesotskiy is someone who makes calculated decisions and carefully plans his investments. Kovrin and his moral dilemmas do not fit a universe like this one – a disappointment to Pesotskiy, Kovrin loses his mind and ends his days in an asylum.

The second Kovrin is played by Odin Byron, in English. This version is told through the eyes of Tanya, both her younger (Viktoria Miroschnichenko) and her older (Gabriela Maria Schmeide) selves[7]. Tanya recognizes Kovrin’s vulnerability and falls in love with it. Odin Byron is one of the leading actors of the Gogol-Centre: an American born actor, he speaks impeccable Russan and exhibits synthetic skills of a theatre performer. His Kovrin strives in the world of theoretical ambiguities and transgressions. Moving faultlessly between Russian and English, with some occasional phrases in German, Byron effoltressly glides over the 36-meter stage of the Palais des Papes. The internal ambiguity and self-awareness mark almost every character he plays, and so they are present within his Kovrin too, who falls in and out of love, in and out of sanity as effoltressly as the actor moves around the stage. While in the first version of the story, we see Mirco Kreibich playing the disintegration of Kovrin’s mind, in Byron’s work we see a weakness of Kovrin’s heart, its susceptibility for breaking. Byron’s Kovrin does break: his madness is manifested in the gradual appearance of Black Monk. Through the change of light and darkness, the monk takes over the stage and the universe.

In the third part of the production, we see another leading actor of the Gogol-Centre – Philipp Avdeev – who comes on stage to offer his own version of the Kovrin character, now in Russian. This one is a cynic and a gambler. He realizes his weakness in the face of the universe but decides to stand against it. This is the angry Kovrin, who dares to challenge his Black Monk.

In the third part of the production, we see another leading actor of the Gogol-Centre – Philipp Avdeev – who comes on stage to offer his own version of the Kovrin character, now in Russian. This one is a cynic and a gambler. He realizes his weakness in the face of the universe but decides to stand against it. This is the angry Kovrin, who dares to challenge his Black Monk.

In the final part of the production, Black Monk takes the centre stage. Played by Gurgen Tsaturyan, this Black Monk does not resort to speech. His presence is manifested through the ritual chanting and movements of the chorus, augmented on stage by music, projections, and light. The monk, whose presence stands both for the darkness of one’s psyche and that of the world, brings (although paradoxically) a sense of relief to Avdeev’s Kovrin. Falling into the whirlpool of his own madness gives Kovrin a sense of freedom, something that he would never experience as an intellectual, a husband, or a gardener. This madness is Kovrin’s ultimate happiness – his giving in to the universe. Here, there is no redemption or forgiveness that many Chekhovian characters dream about. In the world of Serebrennikov’s Le Moine noir, there is only emptiness and darkness.

The production closes with the enigmatic image: the shimmering multitude of the circles of light is projected onto the back wall of the Palais des Papes, the image that evokes the philosophical abstracts of eternity, death and the unknown. Serebrennikov cites his adherence to Buddhism, a system of regulations, moral teachings, and life values which he finds a refuge in. Perhaps the final image of the swirling bodies reflected within the projection of the spinning lights can be read as a reflection of the director’s spiritual convictions or an invitation for our own contemplations on what philosophy, politics and world are about today. Yet, the ending of Le Moine noir remains as open and as enigmatic as its opening: like anything that begins in the middle, this journey ends in the abyss. It unsettles the audience, as it offers us neither moral nor political lessons about the world beyond the walls of the Palais des Papes.

source: Theater Times